The Delhi government implemented the Luxury Tax, also known as “the Original Act,” on November 1, 1996, with the goal of expanding its sources of income. The tax was aimed at a variety of institutions, including hotels, lodging houses, and clubs. Later, on August 9, 2012, the luxury tax’s purview was expanded to include services provided by spas, gyms, and banquet halls. The Delhi Tax on Luxuries (Amendment) Act, 2012 (henceforth referred to as “the Amendment Act”) further altered it.

The Delhi Gymkhana Club, a not-for-profit organisation under Section 25 of the former Companies Act, 1956 (henceforth referred to as “the Act”), recently challenged the legality of an order made by the Commissioner (Entertainment and Luxury Tax) in a decision rendered by the Delhi High Court on November 17, 2023. The luxury tax that was imposed on the club’s operations for the fiscal years 2009–10, 2010–11, and 2011–12 was the main point of contention. The ruling, delivered by Honourable Justices Yashwant Varma and Ravinder Dudeja, explores the complex network of definitions, modifications, and statutes pertaining to luxury taxes.

Delhi Gymkhana Club, the petitioner, challenged the ruling on the grounds that it is a social club that operates on the mutuality principle. The club stated it was properly incorporated in accordance with Section 25 of the Act and, therefore, not liable to pay luxury tax under the Delhi Tax on Luxuries Act, 1996.

Evolution of Luxury Tax Law Pertaining to Clubs and Hotels:

The Delhi Tax on Luxuries Act, 1996, and its 2012 revision were examined in this case. The original act mainly levied taxes on the turnover of receipts associated with hotels’ provision of residential lodging. The 2012 revision, however, expanded the definition to cover spas, health clubs, banquet halls, and gymnasiums.

“The activity of providing residential accommodation and any other service in connection with, or incidental or ancillary to such activity of providing residential accommodation, by a hotelier for monetary consideration” was the definition of “business” in Section 2(b) of the original Act.

The following definitions were also given to the terms “club,” “establishment,” “hotelier,” and “luxury provided in a hotel”:-

The Original Act’s Section 3 outlines the charging provisions and taxes that can be imposed and assessed on a hotelier’s turnover of revenues. The following are the main clauses:

Tax Imposed on Hoteliers’ Turnover:

According to subsection (1), a tax will be imposed on a hotelier’s turnover of revenues, according to the Act’s requirements and the norms that go along with them.

Rate of Taxation and Notification:

The tax rate cannot be more than fifteen percent, according to subsection (2), which also gives the government the authority to periodically announce the exact rate. Depending on the cost of the luxury that each class of hotel offers, different tariffs could apply.

Computation of Charges:

When costs are imposed in a manner other than daily or per room, the proviso under subsection (2) clarifies how the charges are calculated for tax liability. It requires a proportionate calculation based on the entire time the space has been occupied.

Included in Service Fees:

The inclusion of service fees, which are assessed and kept by the hotelier and are not given to the employees, in the costs associated with the opulence offered by the establishment is covered under subsection (3).

Tax on Nonexistent or Concessional Charges:

According to subsection (4), the tax will still be imposed and collected at the rate mentioned in subsection (2) as if all charges were made even if luxury services offered by hotels are not charged or are charged at a reduced cost.

Exemption for Food and Drinks:

If a hotelier is required to pay sales tax under the Delhi Sales Tax Act, 1975, they are excluded from paying tax on the turnover of receipts for the supply of food and beverages under subsection (5).

Handling of Separately Collected Tax:

For the purposes of this Act, tax that is independently collected by the hotelier is not regarded as part of the receipt or turnover of receipts by the hotelier, as stated in subsection (6).

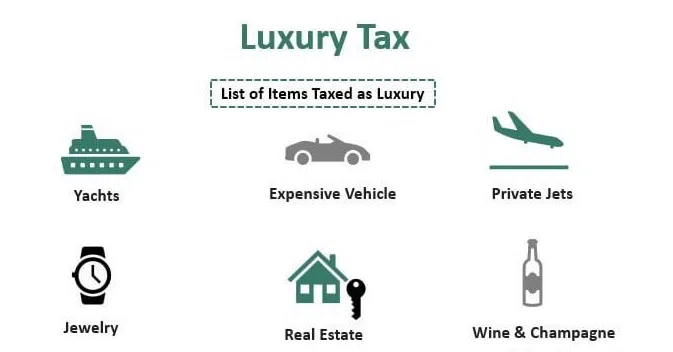

The 2012 Amendment Act created the term “luxury,” which is defined as the use of products, services, real estate, etc. for comfort, pleasure, enjoyment, or consumption above and above what is necessary for survival. Details on specific inclusions under “luxury” are provided for hotels, spas, banquet halls, and gymnasiums.

Amendments to Section 3 – Incidence and Levy of Tax:

The incidence and levy of taxes on a proprietor’s turnover of receipts are described in Section 3. The government is notably empowered to announce the tax rate, which cannot be more than fifteen percent. For varying categories of luxury offered, separate rates can be communicated. The calculation of tax liability when fees are imposed in a manner other than daily or per room is outlined in this section. For tax purposes, service charges that are assessed and kept by the owner but are not given to the employees are considered to be a component of the turnover of receipts. The tax is imposed and collected as if the full charges had been paid, even in cases where luxury is either not charged at all or is charged at a reduced rate. There are tax exemptions available for sales of food, beverages, and specific goods under the Delhi Value Added Tax Act, 2005.

Tax collected separately by the proprietor is not considered part of the receipt or turnover for the purposes of the Act.

Application of Principle of Mutuality:

Mutuality is a legal notion that applies when an organisation, like a firm, takes money from its members and uses it for their advantage. The identity in the nature of those who participate in the excess and those who contribute is the central idea of this concept. In the Royal Western India Turf Club India Ltd. v. Commissioner of Income Tax case, the Indian Supreme Court expounded on this notion.

The Supreme Court clarified that the established company may be viewed as merely an instrument or a convenient agent for carrying out what the members may otherwise do for themselves when there is identification between the contributions and the beneficiaries of the surplus. In summary, the principle of mutuality states that a business should not be taxed on transactions among its members as profit-generating if the business exists for the benefit of its members and there is no profit motivation involved. Any excess is viewed as a return to the donors rather than as a profit for the organisation, with a focus on the reciprocal relationship between contributors and beneficiaries.

Club Facility Luxury Tax:

In the Delhi Gymkhana Club Case, the Delhi High Court offered an analysis that concentrated on the enlargement of the tax levy imposed by the 2012 Amendment Act. With the change, the Act’s definition of a “establishment,” as stated in Section 2(g), was expanded to include activities covered under Sections 2(eb) and 2(g). This meant that in addition to businesses like hotels, banquet halls, gyms/health clubs, and spas were now subject to the tax.

The High Court did note, however, that the term of “luxury” as defined by Section 2(i) include some activities, such lodging or space in a banquet hall, services provided in a fitness centre or gym, lodging and services provided in a hotel, or amenities and services provided in a spa. The petitioner, according to the Court, did not fall within any of these specified activities.

When analysing the definition of “receipt” in Section 2(m), this analysis is essential. The Delhi High Court notes that in order to be subject to taxation, the petitioner—which is classified as an establishment under Section 2(g)—must not only offer luxury but also bring in money or receive payments for doing so. Given that the petitioner’s income did not come from providing a luxury as that term is defined by the Amendment Act, the Court suggested that the petitioner’s earnings were covered by Section 2(m). This distinction is important in figuring out whether the petitioner is eligible for the luxury tax.

A well-known club in Thiruvananthapuram contested the imposition and demand of luxury tax on rent and other fees that the club collected from visitors staying in air-conditioned cottages, air-conditioned rooms, and non-air-conditioned rooms belonging to the club in the case of “Trivandrum Club vs. Sales Tax Officer.” The argument was over the luxury tax that was sought for the rent and other fees that were collected from guests staying in the specified rooms and cottages, not the luxury tax that was payable under Section 4(2A) of the Kerala Tax on Luxuries Act, 1976.

The main question in the case concerned whether the Trivandrum Club, which is a club rather than a hotel, had to pay the luxury tax on room rentals and other fees associated with providing lodging and other amenities to visitors.

In its investigation, the Kerala High Court examined whether the club’s cottages and rooms qualified as a “hotel” for the purposes of Kerala Tax on Luxuries Act Section 2(e). The club argued that it shouldn’t be treated like a hotel subject to pay luxury tax since it didn’t operate in the profitable industry of renting out rooms. Nonetheless, the Court determined that the Act’s definition of “hotel” is wide and includes even guest homes managed by the Government or corporations.

The High Court further underlined that there were particular mechanisms in place for levying a luxury tax on clubs, such as an annual membership tax and a tax on the rent paid for amenities like “auditoriums and kalyanamandapams attached to clubs.”

In the end, the High Court determined that rooms and cottages connected to clubs qualified as “hotels,” which meant they were subject to the luxury tax.

In conclusion, about M/s Mahindra Holiday & Resort India Ltd. The High Court further underlined that there were particular mechanisms in place for levying a luxury tax on clubs, such as an annual membership tax and a tax on the rent paid for amenities like “auditoriums and kalyanamandapams attached to clubs.” In the end, the High Court determined that rooms and cottages connected to clubs qualified as “hotels,” which meant they were subject to the luxury tax. Regarding M/s Mahindra Holiday & Resort India Ltd., in conclusion.In this instance, the High Court highlighted that annual subscription fees or membership fees are not taxable. Rather, the daily fees are established by means of tariffs or fixed prices for every category of lodging in a certain season. According to the ruling of the High Court, the fees that apply when using the privilege are taken into account even while determining liquidated damages for members who are unable to find lodging after a confirmed reservation. The case “Godfrey Phillips India Ltd. v. State of U.P.” has been held in the same manner. The Court argued that the conduct in question is taxable under the Kerala Act’s definition of luxury, which includes lodging for personal use or habitation at a hotel.

Implications for Future Cases:

The Delhi Gymkhana Club case underlines how crucial it is to challenge tax rules from the outset in order to build a solid legal foundation. It also emphasises how tax laws are dynamic and how careful legal analysis is necessary to adjust to them. Future decisions dealing with comparable complexities arising from the ongoing evolution of tax rules will probably highlight the necessity for a comprehensive understanding of mutuality principles as well as statutory modifications.