Our complimentary publications inform you about current developments in the Asian real estate market and key trends in the real estate industry. Sign up to receive them automatically.

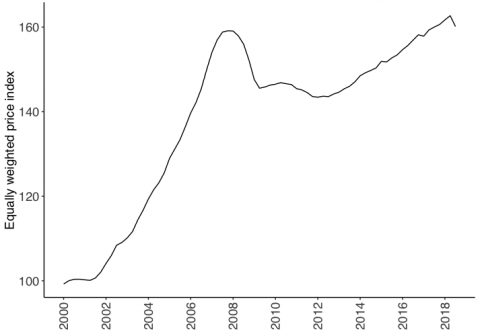

The effectiveness of government policies in stabilizing home prices has drawn massive attention among global policymakers. The attention is justified: according to the IMF, despite ever-tightening policy measures in the post-crisis era, supported by cheap financing, global real house prices have recovered to their 2007 peak levels (see Figure 1). After the subprime crisis, even liberal capitalists admitted that government oversight is necessary to keep the housing sector stable. How governments navigate housing markets into safe waters is becoming a universal concern given the sector's substantial impact on both individual households and the overall economy.

This topic is especially pertinent in China, where real estate accounts for more than 2/3 of households' wealth. As such, the health of this sector has far-reaching financial and social implications. Housing prices in megacities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen have seen significant increases in the past 15 years, with many experts trying to predict how long the trend will last.

Unlike the U.S. and most other Western countries, China runs a unique economic model (usually referred to as "state capitalism" or "socialism with Chinese characteristics") where the government takes an active role in guiding market forces. Its grip on the property market is no exception: the central and local governments have rolled out a series of policy measures in reaction to price increases in major cities over the past decade. These policies include short-term ones that are macroprudential, fiscal, or administrative in nature, as well as long-term ones supporting structural changes. In response to a growingly diversified housing market, they have also been increasingly specific and implemented on a local rather than national level.

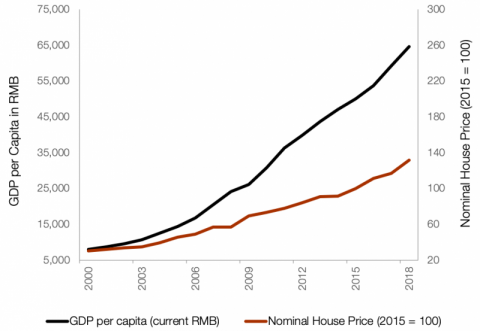

Thanks to interventions by the "visible hand", at the national level, month-on-month and year-on-year price growth rates for commercial residential buildings have stayed around 1% and 10% respectively over the past 10 years. Moreover, this sustained growth in housing prices has been accompanied by equally robust growth in GDP per capita ever since China abolished its "welfare housing" system in 1998 (see Figure 2), indicating a sound and solid housing market.

This ASIA INSIGHTS provides a closer look at the various policy measures employed by the Chinese government to stabilize the housing market, and discusses the effectiveness of these measures in curtailing property speculation and preserving market rationality.

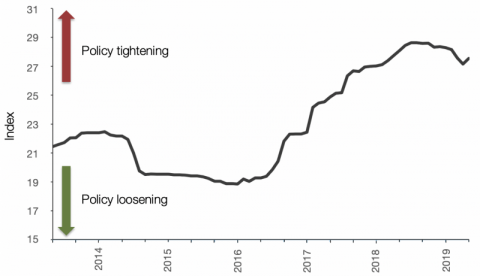

The central government issued tightening measures as early as 2005-2007, the immediate effectiveness of which won popularity among policymakers. During the next 10 years, the central government's attitude shifted back and forth between tightening and loosening, with 2010-2011, 2013, and late 2016-2018 identified as restrictive periods (Koss and Shi, 2018) (see Figure 3). Tightening measures, aimed at holding off demand and reining in prices, were usually short-term oriented.

Figure 3: China Property Policy Index

The General Office of the State Council of the PRC is responsible for setting housing policies at the national level. This General Office is behind some of the most renowned policy announcements such as the "National 10" in April 2010 and the "National 5" in February 2013. Based on these national policies, local governments usually release detailed measures calibrated to their own market conditions.

A policy announcement typically features a mix of measures: squeezing credit, limiting prices, imposing purchase/resale restrictions, and raising taxes or curtailing subsidies. Following is a summary of the impact of each aforementioned measure in past policy announcements:

Credit conditions are measured by both cost of and access to credit. In order to achieve their city's yearly housing price target, each People's Bank of China branch can on its own raise or lower the down-payment ratio and/or the mortgage rate if necessary. In cases where commercial banks are allotted credit quotas, borrowers often face lengthy and stringent scrutiny as quotas shrink. As another frequent measure, commercial housing loans and Housing Provident Fund loans are often granted with different maximum loan amounts, minimum down-payment ratios, and mortgage rate levels, depending on whether borrowers are local or non-local buyers, first- or second-home buyers, or ordinary- or luxury- home buyers. Recognition of a second-home buyer also matters: at times, having a housing loan record (paid off or not) is enough to be considered a second-home buyer even without a current home. Moreover, to crack down on shadow lending, buyers are forbidden from channeling down-payments though real estate brokers, or through peer-to-peer lending and crowdfunding platforms.

Faced with constrained credit conditions, some buyers may bargain harder on price while others may lose the financial means to a home purchase altogether, both of which cases will help to cool an overheated market and curb excess borrowing. Indeed, although the volume of personal housing loans has risen exponentially over the past decade, its growth has been scaled down during periods of tightened credit conditions (2010-2011, 2013, and late 2016-2018) (see Figure 4). Similarly, milder home price growth has historically followed tighter credit conditions with a lag of 9 to 12 months.

Figure 4: Personal Housing Loans to GDP Ratio

Taking Beijing as an example, the down-payment ratio for an ordinary second home was raised to a record high of 60% (for a luxury second home even to 80%) in March 2017; recognition of a first-home buyer also became stricter than ever: those newly-divorced were still considered second-home buyers, closing a previous policy loophole that had couples divorcing in order to qualify as separate households. Consequently, yearly growth in personal housing loans slowed by 25.2 percentage points in 2017, and personal housing loans only accounted for 20.2% of all new loans issued in 2017, a 20.1 percentage point decrease from 2016. Sales prices of newly constructed commercial residential buildings also slowed from a sizeable annual growth of 20.6% in March 2017 to a flattened 0% in December 2017, a proven success of the government in restoring home prices to rational levels.

The second category of measures concerns those limiting prices, the effects of which are straightforward. These measures usually start with a municipal government's yearly housing price growth target, which in most cases does not exceed the city's GDP growth or its urban households' real per capita disposable income growth during the year to ensure housing affordability. Another common effort of the municipal governments to promote affordability involves pre-sale permits, which are only granted if the applied prices do not significantly exceed those of the previous batches or those of the comparable projects. Developers shall stick to the granted prices until their next application, where prices may be increased, but at a speed no faster than the city's urban households' real per capita disposable income growth.

Price limits can also be imposed through land bidding, which takes on one of the following forms: 1) the average (or the highest) home sales price is fixed before bidding, and whoever pays the highest land price wins; 2) land price is fixed before bidding, and whoever promises the lowest average sales price wins; 3) first bid until the highest land price is reached, then bid until the lowest average sales price is reached, and whoever offers both the highest land price and the lowest average sales price wins (criteria other than "the lowest average sales price" also exist: for example, the largest developer-held for-lease area, the largest affordable housing area, etc.); 4) the average (or the highest) sales price is fixed before bidding, so is the proportion of small units (smaller than 90 m2) in the project: over 70%; whoever offers both the highest land price and the lowest average sales price wins. Land auctions done as such are ingenious ways to secure adequate housing supply for low- to middle-income families.

The third category of policies regarding home purchase restrictions (HPR) and resale restrictions is blunt administrative measures. To be eligible for an additional unit, newly-built or second-hand, a Hukou household (a system of household registration that officially identifies a family as residents of an area) shall not already own more than one unit, and a non- Hukou household, provided that it does not already own a unit, shall further present proof of over 1- or 3-year-long income tax or social security payments within the last 2 or 5 years, the actual number of years depending on the city of the non-Hukou household. Details also vary as to the scope of implementation: some cities impose citywide restrictions while others confine them to inner-city areas.

HPR were first introduced by the state government in April 2010 with the benign intention to tame home prices that had swiftly re-emerged from the crisis thanks to China's RMB 4 trillion economic stimulus package during 2008-2009. By October 2011, nationwide 46 cities had implemented their own HPR policies, as a result of which annual home price growth quickly moderated during 2010-2012. Many studies have tried to quantify this observation: Zhang and Zheng (2013), for example, discovered that by suppressing mainly speculative non-local demand, HPR effectively slowed yearly home price growth by 4% to 3%.

The other administrative tool, resale restrictions, can apply heavy income taxes on the sales revenue for units that change hands within 2, 3 or 5 years after ownership certificates have been granted. In more extreme cases, resales of units held shorter than a certain period are barred altogether. Targeting primarily at speculative demand, resale restrictions were found to be the most constructive measure in first-tier cities (Li, 2019), where more than 60% of the demand was investment driven in 2017 (CRIC compilation).

The last category of policies is related to fiscal tools. Land VAT is a progressive tax whose rates increase in tandem with sales prices and as such inflated prices are by design disincentivized. Moreover, a project with significantly higher sales prices than its competitors shall be closely examined for land VAT, whose rates may also be leveled in such a case. Another policy-heavy area involves property tax. Propelled by the need to facilitate supply-side liquidity with less taxes in the transaction phase and the need to reduce local governments' fiscal reliance on unsustainable land sales, the central government has put real estate tax reform on top of its agenda for years. In January 2011, Shanghai and Chongqing started a trial property tax on certain privately-owned homes. Later in November 2013, the introduction of real estate tax (one that combines property tax and land use tax) was brought to the table; the initiative was quickly formalized as the real estate tax law in 2015. Further in 2018, the National People's Congress fast-tracked its legislation agenda with the goal of finalizing the law within the next 5 years.

This new system where tax burdens are balanced out along a property's life cycle will not only boost market liquidity and punish ownership of multiple homes that are often left unattended or used solely as investments, but also enable local governments to restructure their fiscal revenues: less from land sales and more from property taxes, fixing the problem of "overdevelopment in wrong places" that has historically led to "ghost towns" in less-urbanized areas.

Overall, the 5 categories of short-term oriented policies, when applied in combination with one another, proved to have an immediate and evident effect: monthly price growth of newly constructed homes was slowed by 5.5% over 12 months for 17 prime first- and second-tier cities (Li, 2019). By curbing excess borrowing, providing affordable housing, and dampening speculative demand, the "visible hand" has been effectively guiding China's housing market to achieve both growth and stability.

During recent years, realizing that short-term solutions can only restrain demand temporarily, policymakers have been increasingly leaning towards more sustainable measures. Promoting the development of rental housing is one such example. As opposed to the current situation where millions of individual landlords create market supply, commercial rental housing with single ownership and unified operations can provide tenants with more suitable units with better quality, and with safer lease agreements through centralized management.

Boasting nearly 400 million people (30% of China's population), the millennial generation, characterized by high mobility and late marriage and confronted with high barriers to home ownership in the megacities, is a significantly large segment for the development of rental housing. Many pilot cities have zoned collective land for rental projects, while others have required developers to set aside certain GFA for rental housing as part of the land bidding process. For cities that wish to continue reaping the economic gains from a net population influx, especially for second-tier cities and satellite cities surrounding Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, the government has been keen on granting non-Hukou renters equal access to social benefits as local homeowners to encourage the willingness to rent. Other policy incentives include permitting conversions of idle commercial properties to rental housing and granting income tax deductions for renters.

Led by favorable demographics and encouraging policies, China's rental housing has gained momentum since 2015, and is poised to continue its growth in the near future. The development of rental housing is key to tackling supply-demand imbalance in overheated cities and to creating a mature market over the long run.

With a significant amount of household wealth tied up in real estate, Chinese policymakers are extremely wary of the health of this sector. To ensure social contentment, the government will do whatever it takes to keep the housing market stable. Both short- term focused and long-term oriented policy measures have been employed to suppress speculation and address affordability. Thanks to these measures, the Chinese housing market has demonstrated a high degree of resilience to market noises in the past. Moreover, the last 10 years has seen a growingly diversified housing market landscape in China. Even if local corrections in some remote or economically weak regions are inevitable, metro polises with high population influx and solid GDP growth are unlikely to be affected and the chance of a nationwide downturn is slim.

Policymakers of emerging economies often face the tradeoff between short-lived speedy growth and long-lived modest growth. To achieve its yearly GDP growth target at all costs, China has been running a credit-fuelled model since 2008. Rising property prices also powered the growth of a chain of economic activities. However, aware of the danger in blindly chasing after a number, the Chinese government has shifted its focus towards the quality of growth in recent years. Structural changes are being made to facilitate the transition to a more sustainable growth path. Compromises on both GDP growth and property prices can thus be expected: steady and sturdy is better than peak and trough in such cases.

In the meantime, as housing prices moderate in expensive megacities, commercial rental housing presents a unique opportunity for investors. Backed by strong fundamentals, supported by favorable policies, development of rental housing is also the exact kind of structural shakeup needed in the real estate sector, one that echoes with Xi's dictum "Houses are for living in, not for speculation".

Sources

International Monetary Fund; Center for American Progress; China Economic Trend Research Institute; National Bureau of Statistics of China; The World Bank; Everbright Sun Hung Kai; People's Bank of China; Municipal Governments' Websites; Jones Lang LaSalle; South China Morning Post; Financial Times; Nikkei Asian Review; Asia Green Real Estate

Disclaimer

© 2019 Asia Green Real Estate AG, Switzerland. No warranty can be accepted regarding the correctness, accuracy, uptodateness, reliability and completeness of the content of this document. Asia Green Real Estate expressly reserves the right to change, to delete or temporarily not to publish the contents wholly or partly at any time and without giving notice. This document as well as its parts is protected by copyright, and it is not permissible to copy them without prior written consent from Asia Green Real Estate. This material does not take into consideration the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any person that enters into a relationship with Asia Green Real Estate. No representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is made by Asia Green Real Estate regarding future performance. This material is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity that is a citizen or resident of, or located in, any locality, state, country or other jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation or subject Asia Green Real Estate to any registration requirement. The document may contain forward-looking statements that reflect Asia Green Real Estate's current views with respect to, among other things, future events and financial performance. Any forward-looking statement contained in this material is based on our current estimates and expectations and are subject to various risks and uncertainties.